As Christians engaging with philosophy and perhaps becoming philosophers ourselves, the question arises: what is the relation between this study and our faith? Poetically, what does Athens have to do with Jerusalem? Precisely, what does philosophy have to do with theology? When Thomas Aquinas took up this question, he responded with two notions in mind. The first is his one truth principle, which is that truth cannot contradict another truth. The second is the Aristotelian notion of separate sciences, which is that each science (or field of study or organized body of knowledge) has its own method and first principles.

Now, rather than thinking of philosophy as the general love or pursuit of wisdom (which would, of course, include the wisdom and insights of our faith), Thomas thinks of philosophy as a human attempt to know the truth through the exercise of our reason. But there is more to know than simply “running on our own steam”: There are more sublime truths offered to us via our faith, and when we want to apply our reason to understanding these truths more, this is the work that Thomas Aquinas would consider theology. So philosophy studies “what is” as known by human reason, but theology studies God and his relation to creatures as known by God’s revelation. This division is one of method, not content. There is overlap between what we can know by reason and what God reveals to us. For example, through Scripture we can come to realize our souls have some type of existence after death, but we can also learn this truth through studying philosophy.

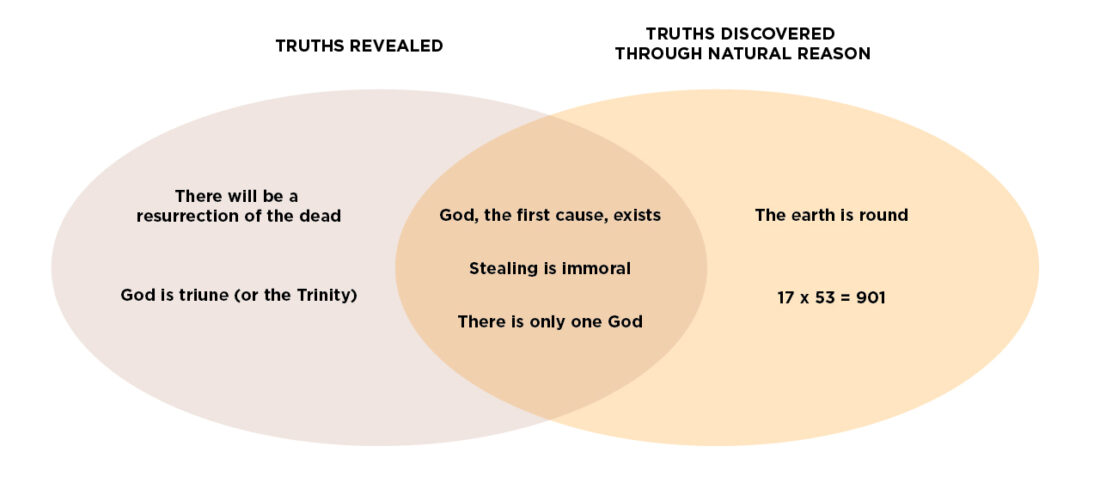

The fourth chapter of Aquinas’s Contra Gentiles which is titled, “That the Truth about God to Which the Natural Reason Reaches is Fittingly Proposed for Belief” examines this “overlap” of content. In this chapter, Aquinas is answering the question, “Why is there this situation that God has revealed to us things that we can know through our reason?” or “Why not have a dichotomy of revealed truth and natural truth?” A Venn diagram is helpful here:

The first circle represents truths learned through God’s revealing them to man, such as that God is triune or that Jesus Christ is both God and man. The second sphere represents the truths that man’s reason can attain naturally or without the aid of divine revelation, such as the earth is round or that things fall at a rate of 9.8 m/s2 on earth. The middle section, where the two circles overlap, represents truths that are discoverable by reason but God has also chosen to reveal them. Examples of these truths of the third kind would be that God exists and that stealing and lying are immoral actions. It is interesting to note that the revealed truths can be metaphysical, scientific, or ethical. So, God through revelation (i.e. the Scriptures and doctrine) gives to men propositions for them to accept as a matter of belief even though man could discover them on his own. So why is this the case? Aquinas writes, “It might perhaps seem to someone that, since a truth can be known by the reason, it was uselessly given to men through a supernatural inspiration as an object of belief.”[1]

Aquinas argues that it is fitting that there be overlap by considering what would happen if it were otherwise. He argues that God revealed truths attainable through natural reason to avoid what he calls three inconvenientia. This word gets translated as awkward consequences, but the word can be translated as results that are unsuitable or dissimilar or inconvenient. The latter translations convey the notion that the consequences would be bad not in the sense of a middle school prom, but bad in the sense that they would not seem to fit with the nature of a loving God. So he argues that the three effects of God not revealing what can be known by reason would be:

1) Few men would have knowledge of him,

2) those who do reach it would take a very long time to do so, and

3) it would be mixed with knowledge that is false which creates an unnecessary doubt.

Let’s now take a closer look as to why Aquinas believes these might occur.

The first unsuitable effect is that few would have knowledge of God if all were left with only their reason to discover the truth. The first reason this unsuitable effect would happen is due to physical conditions. Some humans are sharper and smarter than others. There are people whose intellectual capabilities are not well-equipped to find God in philosophy. It is important to note that Aquinas along with Aristotle considers the highest philosophy to be metaphysics, the study of being qua being, which is also called natural theology. It has this other name is because man must study existence of things beyond their sensible, material existence. And this allows room for studying beings and causes of being who are immaterial. Given how an existence like this would be something divine, we call it a type of theology. Yet it is called a natural theology in that it is studying God by means of only natural reason. This knowledge of God is therefore only attainable through doing the highest and most difficult form of philosophy. If someone is not naturally bright they will not be able to comprehend these highest of truths.

The second reason that causes the first unsuitable effect (too few people) is that not all men would have time to do this philosophy due to the needs imposed upon them by everyday life. Aristotle teaches that philosophy can happen only through luxury. So consider a single mother constantly worried about how she is going feed herself and her child through working some job or a farmer calculating how much seed he needs to plant during the season. The aforementioned examples are busy with temporal matters and therefore will not have the time for thinking of metaphysics or, as Aquinas puts it, “reach the highest peak at which human investigation can arrive, namely, the knowledge of God.”[2]

The third reason not many people would reach knowledge of God is laziness. Knowledge of God through metaphysics requires an intense education in aspects of all kinds of science. Thus, we see later in the Summa Contra Gentiles how dedicated St. Thomas is to the various ideas of motion and physics. Only by considering all sorts of material things that can move in various ways is he able to argue the existence of God through motion. Thus, an extensive study of all types of philosophy is necessary before one approaches the highest one, metaphysics. Interestingly, Aquinas notes that although God has placed in man a natural desire to know (Aristotle proves this by referring to experience that men prefer to see over not seeing), many men deny this!

Moving on, “The second awkward effect,” St Thomas writes, “is that those who would come to discover the abovementioned truth would barely reach it after a great deal of time.”[3] The time it would take for men to grasp this truth would be long not only because they need the right physical and virtuous disposition but also because this lofty use of our mental capacities demands that we be not strongly moved by youthful passions. The knowledge would only be available to us later in life! Again, harkening back to Aristotle who said philosophy can only be done in leisure, Aquinas quotes the Greek philosopher’s work the Physics and takes it a step further. Not only is leisure necessary, but also repose, i.e. leisure used for coming to a state of rest and tranquility. Youth is naturally opposed to this state of equanimity. Not only would few men reach this goal, the knowledge of God, of which Aquinas says “renders men perfect and good,” but it would also take a long time.

The last unsuitable effect is doubt or a lack of certainty regarding the natural truths of the divine. Humans are often wrong about things. At one point in history, we believed the sun circled around the earth. We find then that our investigations into things are mixed with some falsity. This happens, according to Aquinas, “due partly to the weakness of our intellect in judgment, and partly to the admixture of images.” Upon reflection, many of us will find we are guilty of this admixture of images: When we try to speak of God as being one, all-powerful being who created and gives existence to all creation, we might picture in our minds a shiny, circular thing, surrounded in darkness and shooting out light or something. In any event, since men’s minds are “ignorant of the power of demonstration,” they are capable of doubting wise men who profess that there is a God. This situation is exacerbated by the fact that there are many men professing to be wise, and each provides his own type of doctrine. Among these different doctrines we find that truths can be mixed with falsehoods, which are argued by sophistry or based on a bad opinion. So when these different doctrines are mixed with both demonstrable truths and falsehoods, it gives the demonstrable truths a bad presentation allowing others to doubt unfairly the whole.

“That is why,” St. Thomas concludes, “it was necessary that the unshakeable certitude and pure truth concerning divine things should be presented to men by way of faith.”[4] It is for our benefit, then, that God revealed some naturally knowable truths to man. Aquinas refers to God when helping man as the divine Mercy. By including some natural knowledge of God as part of revelation, which is to be taken by faith, God unites the truths, unites the people (or Church), and aids us in avoiding uncertainty.

Aquinas ends with two scripture quotes. “Hence it is written: “Henceforward walk not as the Gentiles walk in the vanity of their mind, having their understanding darkened” (Eph. 4:17-18). And again: “All your children shall be taught of the Lord” (Is. 54:13).” God revealed these things for all people, both the philosopher and the common man. A Christian philosopher is therefore someone who is aided by faith not just in emotional or tribal support but in a rich intellectual way.

Rory O’Donnell is a PhD candidate in philosophy at Marquette University, a senior lecturer for the Pacifica Center for Philosophy + Theology, and is currently teaching philosophy and theology at Bishop Ireton High School and Christendom College in Virginia.

Image: Detail of St. Thomas Aquinas, 1476, by Carlo Crivelli.

[1] St. Thomas Aquinas, Summa Contra Gentiles (Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press, 2009), ch. 4, section 1, pg. 66. All citations henceforth shall be from this edition and noted by chapter and paragraph.

[2 ]Aquinas, SCG, 4.3.

[3] Aquinas, SCG, 4.4.

[4] Aquinas, SCG, 4.5.