Bringing Together What Is Being Torn Apart Means Understanding Theophany.

The-oph-a-ny (noun): a visible manifestation to humankind of God or a god.

In our age, the proliferation of various new age ‘spiritualities,’ the standing suspicion of the “institutional” Church, the ease with which people identify as ‘spiritual but not religious,’ and even the rows of self-help books in your local bookstore, speak of the failure to satisfy humankind’s hunger for theophany. To understand the universality and centrality of theophany, we must comment on how it appears in various distinct yet related contexts: (1) the history of philosophy, (2) the Old Testament, (3) the person of Jesus Christ, and (4) the spiritual and ascetic tradition.

The intellectual and spiritual tradition of the West (Greek and Latin) depended upon a cosmic vision of the entire universe as one of theophany. In other words, every fiber of reality was open to, and pointed toward, an encounter with transcendence. The central philosophical questions in the historical period when this view was dominant were about how to best explain that reality and what steps were needed to fully experience it.

The Greek philosophical tradition which has as its foundation in Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle was fundamentally ‘realist’ in its outlook, which is to say it believed that our words and concepts about things in the world are objective and reflect a transcendent reality that remains unchanged despite changing fashionable conventions or subjective preferences. The famous way this realism was expressed was through Plato’s theory of the forms, literally in ancient Greek: ideas. Everything that exists displays some kind of idea, a universal characteristic of intelligibility (i.e. knowability), which makes that thing exist and allows the mind to know it. As an example, every instance of a cat reveals the idea of Cat, the very intelligibility of Cat, which not only makes particular cats exist but is also what you know when you know the definition of Cat-ness. For Plato and his inheritors, the Form of Cat allows you to say that the cat you know in Washington is the same reality as another one in Paris. There is such a thing as objective ‘cat-nature’ which we can track in the world.

Over time, philosophers situated these ideas in the mind of God. The consequence is not only that God is the cause of all that exists, but that all things reflect God in some limited way, just as we might say a piece of art reflects the life and mind of the artist. In short, to experience and know something as mundane as a cat comes to have deep spiritual significance since the experience and knowledge in question is not just of cats, but also of God. Thus, for ancient philosophy, these Forms or ideas were inevitably an expression of God’s relationship to the universe. If this universe is a manifestation of God, then God is not an entity situated somewhere in the universe (a point missed both by many atheists and theists in their debates on the existence of God), nor is each individual thing in the universe the same as God (monism), nor is the universe as a totality God (pantheism), nor is God something ‘outside’ the universe (dualism); rather all things in the universe, and the universe itself, is a theophany: a manifestation of God. Consider the artist analogy again: the artist is not literally contained in their art (contra the atheism/theism debate), nor is each individual piece of art synonymous with the artist (contra monism), nor is all their art taken collectively exhaustive of the artist (contra pantheism), and nor is the artist a foreign reality from their art (contra dualism). The art is a manifestation of the artist. In terms of God and the universe, all things point to transcendence. Everything has a spiritual dimension. To adopt any of the mentioned positions, therefore, is to make a serious philosophical error and to misunderstand the universe.

Second, if the above can roughly be considered a ‘cosmic’ or ‘metaphysical’ vision of theophany, then what is referred to as the Old Testament, or the Hebrew Bible, displays an even more intimate, ‘scriptural’ understanding of theophany. Many Westerners are familiar with these stories, but perhaps have missed their significance and the role they play through the various books of the Old Testament. If one were to ask a layman what these texts were about the answer would likely refer to God’s covenant with Israel, or perhaps the importance of the Mosaic Law as enshrined in the ten commandments. Yet, curiously enough, very few Old Testament episodes are dedicated to such things. In fact, the ten commandments only appear twice throughout the entire Old Testament! In contrast, consider Moses’ encounter with God on Mount Sinai. While the ten commandments occupy a single chapter (Exodus 20), Moses’s personal encounter with God on the top of the mountain occupies the rest of the book (Exodus 24-40). It is here that he is seen “eating and drinking” before the divine throne that we find the detailed description of the tabernacle, which would later become Israel’s Temple, and we are told of Moses’s vision of the divine Glory (kavod). In other words, Exodus has less to do with law and more to do with theophany via temple worship of God. The greater focus given to these episodes should influence our understanding of God’s law. Morality or ethics is not simply about our legal status before a divine judge, or being ‘good’ in the sight of God, but more about the conditions for entering the heavenly Temple and encountering the Divine, i.e. experiencing personal theophany. Perhaps the modern reader reverses the significance of these sections because we simply have no clue how else to think of the ten commandments outside of a legal framework.

This ‘theophanic’ emphasis is not limited to a few chapters of Exodus, but remains a consistent theme throughout the rest of the Old Testament. Abraham entertains angels that are referred to as ‘the Lord’ (Genesis 18); Jacob sees a heavenly ladder and has a mysterious fight with God (Genesis 28 and 32); Isaiah has a vision of the seraphim around the divine throne (Isaiah 6); Ezekiel sees a divine chariot (Ezekiel 1); Daniel comes into contact with the ‘Ancient of Days’ (Daniel 7)—and these are only some of the highlights. In each case, there is an extraordinary vision of some kind wherein the visionary is transformed by divine encounter. We often think of these instances as miraculous, if not downright mythical, and certainly not something relevant to us. But we should perhaps ask not first whether they are true, or possible, but rather what would it mean for them to be true? Let us not, then, deny that they are positively bizarre, but ask whether their being bizarre has more to do with us than with them. Now that is an interesting philosophical question.

We find that theophanic themes are only heightened when we turn to the New Testament. The basic Christian claim was that Jesus of Nazareth was the messiah, the anointed one (christ), of Israel, somehow fulfilling in his person all of Israel’s expectations about God. Hence, how one interprets the Old Testament greatly affects how one anticipates and then recognizes the fulfillment of Israel’s expectations in Jesus. The life and death of Jesus and those who followed him likewise demonstrate a considerable occupation with theophany. Jesus inaugurates his ministry with his baptism in the Jordan by John, where the heavens open and God the Father proclaims him his beloved Son as the Holy Spirit anoints Jesus in the form of a dove. Not only would this episode serve as the basis for the Christian doctrine of the Trinity, but for the universal practice of baptism in the name of the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. Most importantly, this episode is a textbook case of theophany, a manifestation of not just the voice of the Father, but of the special role of this person Jesus, and an intimation of his relationship to God as his ‘beloved Son,’ emphasized through the visible descent of the Spirit. To the present, the baptism of Jesus is celebrated throughout the Christian world by the name of Theophany (in the East) or Epiphany (in the West).

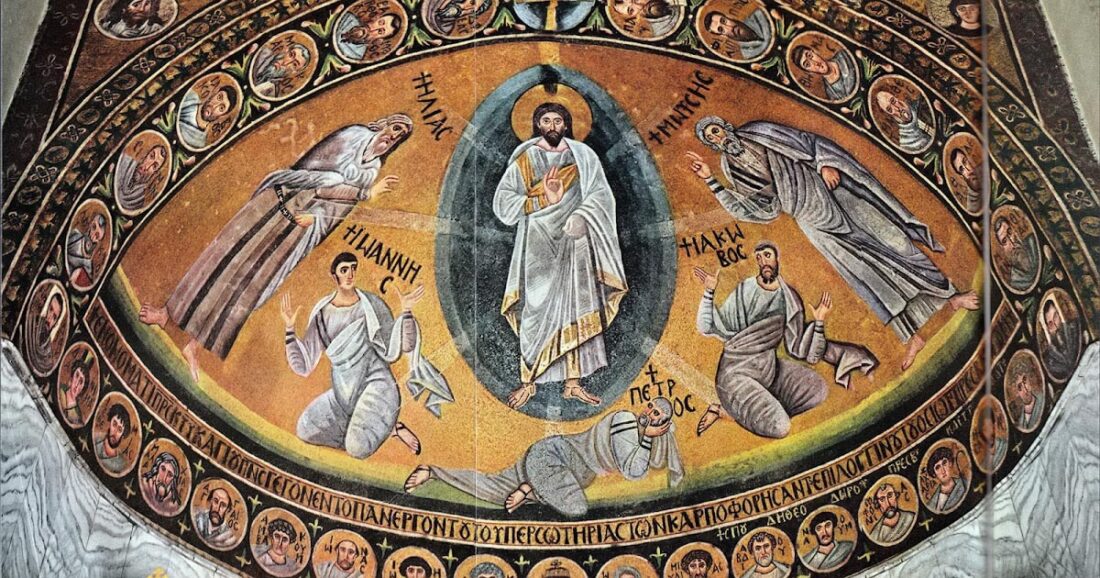

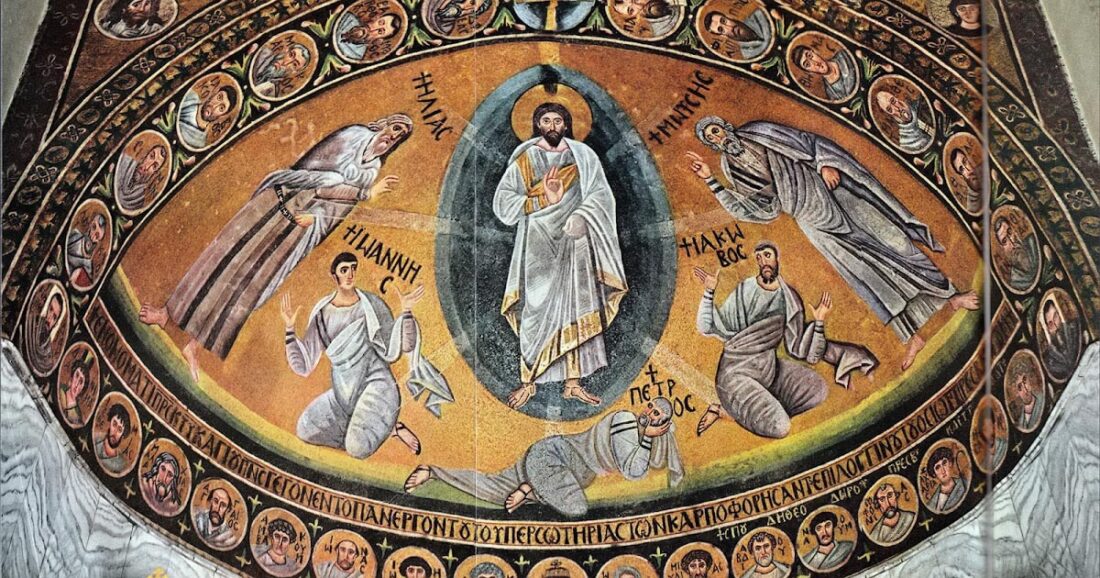

Even more notably, later in Jesus’ ministry he ascends a mountain (Mount Tabor) with his disciples and is transfigured before them: engulfed in glorious light and clothed in shining garments of white. Yet he is not alone, but flanked by Moses and Elijah. This episode has often been interpreted as representing the fulfillment of the Law (Moses) and the Prophets (Elijah). While that is true, the more obvious parallel is that both these figures are paradigms of divine vision and experience. In particular, the entire episode is highly reminiscent of Mount Sinai, where, as we’ve seen in Exodus 24, Moses ascends the mountain and encounters God. So, what is the purpose of the transfiguration? It proclaims that this person, Jesus of Nazareth, is none other than the same divine reality experienced by the patriarchs and the prophets. He is the divine glory (kavod) experienced on Sinai and in the other divine visions. He is, in short, the Glory of the Lord now dwelling in human flesh and accessible to all. However, the radicality of the early Christian proclamation was not that Jesus had been transfigured on Mt Tabor, but that the true divine throne where God takes his kingly seat is the cross. Consider the episode. During Jesus’ trial, he is robed in purple, crowned with thorns and sent to Golgotha (yet another mountain!) to be crucified. He is lifted high on the cross, the sky is darkened, and as he breathes his last the Temple curtain is rent—which is the same Greek word used to describe the opening of the sky during his baptism. In the Gospel of Mark and Matthew, the centurion by his side proclaims him “the Son of God,” another echo of the Father’s proclamation at his Baptism.

What are we to make of this? As can probably be adduced at this point, the major ‘highlights’ of Jesus life are theophanic. The connection between Jesus and the Old Testament is theophany. The incarnate Jesus, in his very taking of human flesh, is a walking theophany. Nowhere is the theophany more heightened, more intense, than in Jesus crucified, which brings the Old Testament imagery of mountaintop theophany together with the theophanic person of Jesus Christ. Per St Paul, the scandal of Christianity was that the Glory of Mt Sinai was crucified on Golgotha (1 Corinthians 1:18-25). Even more radically, the heart of the early Christian gospel was that an average Galilean peasant could access the Glory of Sinai, the Glory hidden in the Holy of Holies in the Jerusalem Temple, by uniting their death with Jesus Christ’s. The paradox, it would seem, is that death has become a vehicle for theophany instead of its opposite; as the psalmist cried, “for in death there is none that is mindful of Thee, and in hades who will confess Thee?” (Psalm 6). God has filled even death with divine Glory.

This leads us to the fourth and final element: that the purpose of the Christian Church is to protect, preserve, pass down, and enable the experience of theophany for regular believers. The mission of the Church is already evident in the New Testament. On the Road to Emmaus, the disciples do not recognize the risen Jesus until they break bread and open the scriptures (Luke 24)—the very things Christians do together when meeting for worship. Again, recall Moses “eating and drinking” on Sinai and the Last Supper of Jesus. It is within this sacramental context that believers are capable of experiencing theophany. In the life of the Church, men and women are not only emboldened to spread the message of Christ, but to become vehicles of theophany themselves. St Paul speaks of being caught up to the “third heaven” and experiencing mysteries beyond comprehension (2 Corinthians 12). St Stephen, when he is being stoned, has a vision of the enthroned Jesus (Acts 7). In the earliest Church Fathers, St Ignatius of Antioch embraces his impending death as a participation in Christ and the opportunity to ‘become truly human’ (Letter to the Romans). St Athanasius of Alexandria, one of the great defenders of the divinity of Christ, spoke of St Antony the Great, a desert monk, emerging from his desert warfare as one coming out of a shrine, radiant, and in complete equilibrium and union with nature (Life of Antony). Crucially, St Athanasius spoke of heroes like St Antony and regular Christian believers as proclaiming the truth and power of Christ’s conquest of death in their own bodies (On the Incarnation). In other words, the concept of ‘saints’ in early Christianity was rooted in the idea that regular human beings can experience, and even become the site of, theophany. This trajectory continues down the centuries in the likes of St Symeon the New Theologian (12th century) who claimed to have visions of divine light. In short, theophany is the heart of the spiritual, ascetic, and ‘mystical’ tradition of Christianity.

Our aim here has been to try to demonstrate briefly the under-appreciated centrality of theophany for Christians and their Hellenic and Jewish forebears, be it the metaphysical theophany of the philosophers, the scriptural theophany of the Old Testament, the Christological theophany of the New Testament or the personal theophany experienced through the Church. Our curriculum at The Center for Philosophy + Theology aims through its offerings to carefully unpack these and other themes for the sole purpose of “bringing together what is being torn apart.” While certain courses will consist of more sustained treatments of the concept of theophany, others provide necessary philosophical and theological context. In either case, all our courses aim in one way or another to guide the participant into a robust understanding of the Christian tradition and to see it in a new light. Likewise, all scholarly contributions to the Center are meant to continue this vision and unpack it in other areas of philosophy and theology. In the end, our hope is that participants will be in a better position to understand what I have laid out here and to evaluate it for themselves.

That process of evaluation will involve a host of reconsiderations of fundamental philosophical and theological questions, considering especially how they might bear on our current historical moment. For instance, if we see the history of philosophy and theology as fundamentally about articulating and preserving theophany, seeing ‘theophanically,’ if you will, then how does that bear on the nature of our universe and our place in it? What does it say about the existence and nature of God, and God’s relationship to the cosmos? How does it affect our account of human nature and humanity’s highest aspirations? Does it change how we think about ethical life and the pursuit of being good? Does it reframe our knowledge of the cosmos and our faculties of reason to accurately map reality? Is faith involved in this process at all and, if it is, is it something alien to reason? How does it change how we interpret scripture, and how those interpretations might bear on scientific accounts of material reality? How should we think about nature, and something being ‘natural,’ and especially our relationship to nature? Do answers to these questions radically impact our daily life, or are they, in the end, a hopelessly abstract intellectual exercise? Finally, how should we interpret the experiment that is modern philosophy and its rejection of this tradition? Is such an experiment ultimately a triumph of progress, or is it perhaps something that we should be concerned about? These are but a few of the questions demanding reconsideration.

If what has been stated here peaks your curiosity, leaves you with unanswered questions, or speaks to your soul, then I wholeheartedly encourage you to get in touch with us and consider accessing our curriculum. We do not presume to be the end of your journey, but the beginning of it. Know well that we are along the journey with you, and that this Center is the product of a host of minds and hearts who themselves have thought this material worth wrestling with, of which I am small part, and I am especially thankful to the leadership, lecturers, faculty, production crews, those behind the scenes, and especially its generous donors, all of whom make it possible.

We invite you to join us, for we have saved you a seat.

Alexander Earl

Director of the Pacifica Center for Philosophy + Theology